In the twenty or so moves I've made over the past five years, I've learned two things: 1)The more you open yourself up to people and places, the harder it is to leave them. 2) Leaving is never easy. I had hoped to take you guys from skinny-dipping in Vermont to riding on the back of a stranger's bicycle in Berlin, from Shankill Road in Belfast to the Christmas Market in Edinburgh. I wanted to show you Vermont in January and my cross-country road trip to L.A. with my mom. I have photos for you of my first garden, my family's trip out on Lake Mead, my Peace Corps invitation, and my adorable dog. In this last few hours I have here, though, I won't attempt such feats. I find myself, instead, wanting only to say 'thank you' to all of you--a gratitude which I am ill-equipped to express.

From gifts to dinners to parties to knot-tying lessons to help with shopping and packing to encouragement, letters, and phone calls...you all have made this somewhat impossible dream possible. This move was one in which I had time to truly open myself up to the people and places around me, and although it has made the goodbyes harder, I have learned that in doing so, I have found in all of you great strength and support as I step out into the unknown. My gratitude and love run more deeply than I can tell you. I look forward to the conversations I will have with each of you over the next two years. Much love, and, well, peace.

P.S. Come visit!

Friday, September 26, 2008

Sunday, September 21, 2008

Sunday, September 14, 2008

Proximity

When I sat down at the table and finally lifted my camera and daypack from around my shoulders, I pulled out the birthday card my mom had stuffed in the top of my backpack just two nights before. I had saved it all day, promising myself to fulfill the vow I'd made that I'd take myself out to a nice dinner to celebrate. When I opened the card, a tinny rendition of "Happy Birthday to You" rang out across the almost-empty restaurant. It was late; I had lost track of time wondering through the streets of Berlin, my headphones blaring, a camera lens framing my view. I slammed the card shut, blushing and--admittedly--chuckling slightly at the possibility that this was, in fact, the exact scene my mom had pictured when she'd picked out a card for my European birthday. Although the intimate Italian restaurant with its dark wood interior left little room for the noise to escape, my small serenade hadn't drawn the attention of the only other couple in the room. From behind the bar, though, the waiter caught my eye, smiled slightly with the same warmth with which he'd coaxed me in off the street.

"Buona sera," he'd said from behind the outdoor menu where I stood translating dish after dish, tired after a day of calling on old high school and college German to get around the city. I pulled my headphones from my ears, surprised to see him standing before me from out of nowhere. "Moechtest du essen?" he asked. "Bitte." He'd led me to the last table in the back corner of the restaurant, brought me the glass of merlot I'd ordered, and watched me from behind the bar, where he stood drying and re-drying wine glasses.

He took my order, poured me another glass of wine. "Kommst du aus Daenemark?" he asked. "Nein, ich bin Amerikanerin." He was surprised, perhaps thrown off by my dark hair, round cheeks, and strange accent. He was Turkish, I learned, and enjoyed visiting Berlin, but was tired of living here, working in a restaurant. He returned to my table often, lingering a bit longer each time, returning always with a fresh set of questions. What was I doing in Berlin? Did I like the city? What was I doing out at a restaurant all alone? Simple questions with such complex answers.

I watched as he served the couple at the adjacent table a pair of after-dinner shots, a restaurant tradition. "Wie alt bist du heute?" he asked. He had been excited to hear that it was my birthday, and he seemed to enjoy my wanton ordering, the unselfconscious flagrance with which I ordered an entire pizza, another glass of wine--the decadence of an Amaretto Eis. "Drei-und-zwanzig," I said. Twenty-three. Again, simple--the image I had of twenty-three; again, complex--the life I was leaving behind with twenty-two.

We fell into conversation when the couple at the next table had left. The two of us, the candle-lit room, the broken German and English with which we danced around one another: I giggled, brought a hand to my lips. A man came and sat at the bar, and though the waiter left to serve him, he held my gaze as I sipped lazily from my glass, savored the last creamy bites of desert. I turned to peer at the moon shining over the dim lights of late-night Berlin.

He brought two shots to my table and toasted with me to my birthday. We clinked the tiny glasses together, threw back the thin liquid, and inhaled deeply. I nodded, closed my eyes, and smiled. He leaned in and whispered to me: he would be off soon, would I wait for him if he brought me another glass of wine.

I waited for him by a drugstore behind the restaurant as he locked up for the evening. It was dark as I watched him come towards me from the around the side of the building; the city was sleeping. I knew this scenario well; from writing to parties, most of my life over the past year had taken place while others were sleeping. He held my hand, led me to a bench beside the ever-vigilant DDR TV tower. Water tumbled from a fountain across the clearing. He leaned in, kissed me deep. I ran my hand over his shaved head. Skin.

I pulled him from the bench, led him farther down the lane to the sidewalk by the road. We walked a bit farther--talking, laughing. He took me to the left and down a narrow tree-lined path beneath early fall branches. The path opened into a clearing; he pulled me close, kissed me again. This is what I'd wanted in Europe, the chance to disappear with romantic strangers, time to be frivolous and to go wherever my days took me. I had come at a sprint, trying to shirk the heft of the past several years.

I want, I want, I want, I thought of the Turkish man with the kind eyes. I felt his hand gentle on my cheek, began to relax into him. But I need, came a certainty from the pit of my stomach. I needed more than a simple fix; I needed something that was much harder to want than this. I pulled away, brought my hand to my face, for a moment still disoriented--lost in my own senses. "I'm sorry," I said, "I'm sorry; ich muss jetzt gehen." Several excuses came to mind too easily, and I laid them out and in too quick succession. I turned before he could register my words and began down the path.

"Jennie," he called after me, a name which was a close approximation of me but which I now knew wasn't me. I turned to face him, already a different person from the girl he'd met a few hours before--the 'Jennie' who had come to him searching for something he couldn't give me. "Jennie," he said again, and I saw in his eyes a version of myself. He wanted to show me the city, he said, and I pictured for a moment his version of the city. I had spent years creating versions of myself, envisioning the world through other people's eyes. But now I had made it all the way across the Atlantic alone. I couldn't afford to choose blindness now, no matter how romantic someone else's vision. A version of myself would always be easier than figuring out the whole on my own, but it would also always be a poor substitute for what else I might find along the way.

I looked back at the man who had led me down this path, promised to meet him the next morning back behind the restaurant--a small transgression I haven't forgotten. I knew then I wouldn't see him again, except, perhaps, for the next evening, when I'd catch his eye from across the street from the restaurant where he'd stand greeting guests. We'd nod and smile at one another, or so I'd like to think, and I'd continue on alone, seeing the world, as I had to, through my own eyes.

Thomas Hoepker exhibit I stumbled onto and where I spent most of my 23rd birthday.

Beautiful gallery, exquisite photojournalist.

"Buona sera," he'd said from behind the outdoor menu where I stood translating dish after dish, tired after a day of calling on old high school and college German to get around the city. I pulled my headphones from my ears, surprised to see him standing before me from out of nowhere. "Moechtest du essen?" he asked. "Bitte." He'd led me to the last table in the back corner of the restaurant, brought me the glass of merlot I'd ordered, and watched me from behind the bar, where he stood drying and re-drying wine glasses.

He took my order, poured me another glass of wine. "Kommst du aus Daenemark?" he asked. "Nein, ich bin Amerikanerin." He was surprised, perhaps thrown off by my dark hair, round cheeks, and strange accent. He was Turkish, I learned, and enjoyed visiting Berlin, but was tired of living here, working in a restaurant. He returned to my table often, lingering a bit longer each time, returning always with a fresh set of questions. What was I doing in Berlin? Did I like the city? What was I doing out at a restaurant all alone? Simple questions with such complex answers.

I watched as he served the couple at the adjacent table a pair of after-dinner shots, a restaurant tradition. "Wie alt bist du heute?" he asked. He had been excited to hear that it was my birthday, and he seemed to enjoy my wanton ordering, the unselfconscious flagrance with which I ordered an entire pizza, another glass of wine--the decadence of an Amaretto Eis. "Drei-und-zwanzig," I said. Twenty-three. Again, simple--the image I had of twenty-three; again, complex--the life I was leaving behind with twenty-two.

We fell into conversation when the couple at the next table had left. The two of us, the candle-lit room, the broken German and English with which we danced around one another: I giggled, brought a hand to my lips. A man came and sat at the bar, and though the waiter left to serve him, he held my gaze as I sipped lazily from my glass, savored the last creamy bites of desert. I turned to peer at the moon shining over the dim lights of late-night Berlin.

He brought two shots to my table and toasted with me to my birthday. We clinked the tiny glasses together, threw back the thin liquid, and inhaled deeply. I nodded, closed my eyes, and smiled. He leaned in and whispered to me: he would be off soon, would I wait for him if he brought me another glass of wine.

I waited for him by a drugstore behind the restaurant as he locked up for the evening. It was dark as I watched him come towards me from the around the side of the building; the city was sleeping. I knew this scenario well; from writing to parties, most of my life over the past year had taken place while others were sleeping. He held my hand, led me to a bench beside the ever-vigilant DDR TV tower. Water tumbled from a fountain across the clearing. He leaned in, kissed me deep. I ran my hand over his shaved head. Skin.

I pulled him from the bench, led him farther down the lane to the sidewalk by the road. We walked a bit farther--talking, laughing. He took me to the left and down a narrow tree-lined path beneath early fall branches. The path opened into a clearing; he pulled me close, kissed me again. This is what I'd wanted in Europe, the chance to disappear with romantic strangers, time to be frivolous and to go wherever my days took me. I had come at a sprint, trying to shirk the heft of the past several years.

I want, I want, I want, I thought of the Turkish man with the kind eyes. I felt his hand gentle on my cheek, began to relax into him. But I need, came a certainty from the pit of my stomach. I needed more than a simple fix; I needed something that was much harder to want than this. I pulled away, brought my hand to my face, for a moment still disoriented--lost in my own senses. "I'm sorry," I said, "I'm sorry; ich muss jetzt gehen." Several excuses came to mind too easily, and I laid them out and in too quick succession. I turned before he could register my words and began down the path.

"Jennie," he called after me, a name which was a close approximation of me but which I now knew wasn't me. I turned to face him, already a different person from the girl he'd met a few hours before--the 'Jennie' who had come to him searching for something he couldn't give me. "Jennie," he said again, and I saw in his eyes a version of myself. He wanted to show me the city, he said, and I pictured for a moment his version of the city. I had spent years creating versions of myself, envisioning the world through other people's eyes. But now I had made it all the way across the Atlantic alone. I couldn't afford to choose blindness now, no matter how romantic someone else's vision. A version of myself would always be easier than figuring out the whole on my own, but it would also always be a poor substitute for what else I might find along the way.

I looked back at the man who had led me down this path, promised to meet him the next morning back behind the restaurant--a small transgression I haven't forgotten. I knew then I wouldn't see him again, except, perhaps, for the next evening, when I'd catch his eye from across the street from the restaurant where he'd stand greeting guests. We'd nod and smile at one another, or so I'd like to think, and I'd continue on alone, seeing the world, as I had to, through my own eyes.

Thomas Hoepker exhibit I stumbled onto and where I spent most of my 23rd birthday.

Beautiful gallery, exquisite photojournalist.

Tuesday, September 9, 2008

Backtracking

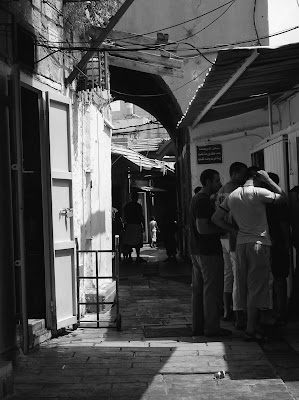

September 2007: I walked through the narrow stone pathways of the shuk, an unfortunately obvious tourist, my eyes wide to a culture so unfamiliar--a challenge as of yet unexamined, a small entrance into a life completely outside my own. The gritty stone architecture, the winding alleys leading to the Via Dolorosa, brought to mind vivid biblical imagery from mornings spent in Sunday School years ago. Funny how the only comparison I could find to the culture around me came from stories I'd heard as a child. I had no other access to this place, these people so unlike the Israeli images in the U.S. news. Eager shopkeepers brought us in, offered cold water and proud tours of their wares. Children ran through the streets alongside nuns and tourists, young women in jilbab and old men standing in shaded doorways.

Moving easily among the four quarters of the city, I noticed not only the striking differences in the smells, sights, and sounds of each distinct cultural enclave, but also the harmonious way in which the boundaries collided, crossed, blurred, and overlapped with one another. Inside the walls of the shuk, four divergent cultures converged and coexisted, worked around each other and even in conjunction with one another.

Our trip was short, certainly not long enough for me to see the country with the eyes of anything more than a tourist, but it still took us far into the corners of this tiny nation we'd come to visit. In the north, the Roman ruins and the impossibly blue sea dominate the landscape. A trip down into the underground sea caverns at the north border could be a beautiful Mediterranean vacation stop until you emerge to the sight of the Lebanese border, a brief reminder that this place is haunted by the ever-vigilant ghosts of war. A trip through Haifa is a balmy afternoon drive until a collapsed roof unavoidably conjures the possibility that it wasn't simply a tree that fell on this house, but rather, a bomb. Reminders of war temper the beauty of the land, never far from consciousness, never long forgotten or overlooked.

On the way south, the reminders become more overt, intentionally unmistakable. As we drove through Bedouin territory with the sides of the road lined with the temporary settlements of traditional Arabic nomads, red signs began to dot the landscape, their white writing warning travelers in three languages not to enter the militarized zone beyond the roadside. Soldiers manned a large weapon tracking cars and buses, tourists and locals, passing through a border check on the road to the Dead Sea. Everywhere, it seemed, small reality checks kept us reigned in, aware of the truth which lay just beyond the towering red rock peaks.

Israel is a small country, too compact to hide its political skeletons, too close to its war to separate itself from the struggle. But there is something to be taken away from all this proximity, from the difficult history and convergence of cultures that make up this mish-mash of people. I won't venture to draw a conclusion on what it all means, but as I traveled from my own 'war-torn' country into theirs, I couldn't help but wonder which of us had a better chance at peace in the long run. I couldn't help but know that this was a place which would stick with me for a long time to come.

Moving easily among the four quarters of the city, I noticed not only the striking differences in the smells, sights, and sounds of each distinct cultural enclave, but also the harmonious way in which the boundaries collided, crossed, blurred, and overlapped with one another. Inside the walls of the shuk, four divergent cultures converged and coexisted, worked around each other and even in conjunction with one another.

Our trip was short, certainly not long enough for me to see the country with the eyes of anything more than a tourist, but it still took us far into the corners of this tiny nation we'd come to visit. In the north, the Roman ruins and the impossibly blue sea dominate the landscape. A trip down into the underground sea caverns at the north border could be a beautiful Mediterranean vacation stop until you emerge to the sight of the Lebanese border, a brief reminder that this place is haunted by the ever-vigilant ghosts of war. A trip through Haifa is a balmy afternoon drive until a collapsed roof unavoidably conjures the possibility that it wasn't simply a tree that fell on this house, but rather, a bomb. Reminders of war temper the beauty of the land, never far from consciousness, never long forgotten or overlooked.

On the way south, the reminders become more overt, intentionally unmistakable. As we drove through Bedouin territory with the sides of the road lined with the temporary settlements of traditional Arabic nomads, red signs began to dot the landscape, their white writing warning travelers in three languages not to enter the militarized zone beyond the roadside. Soldiers manned a large weapon tracking cars and buses, tourists and locals, passing through a border check on the road to the Dead Sea. Everywhere, it seemed, small reality checks kept us reigned in, aware of the truth which lay just beyond the towering red rock peaks.

Israel is a small country, too compact to hide its political skeletons, too close to its war to separate itself from the struggle. But there is something to be taken away from all this proximity, from the difficult history and convergence of cultures that make up this mish-mash of people. I won't venture to draw a conclusion on what it all means, but as I traveled from my own 'war-torn' country into theirs, I couldn't help but wonder which of us had a better chance at peace in the long run. I couldn't help but know that this was a place which would stick with me for a long time to come.

Early morning, Jerusalem shuk

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)